A Place Called Utopia

Painter, sculptor, photographer, essayist, and poet Dr Victoria King contacted Cool Earth with a request to spread awareness about the work we do at a recent exhibition. A Place Called Utopia: Aboriginal Art from Australia, at the Saul Hay Gallery in Manchester, showcased some of the most prolific Australian Aboriginal artists. We caught up with Victoria to find out more about the exhibition and why she chose to support Cool Earth.

I have been passionate about the natural world all my life and a professional artist for 50 years, but during the 25 years that I spent in Australia my perception of the land and art radically changed. When I returned to live in England in 2018, I realized that very few British people had ever seen contemporary Aboriginal art, or, if they had, knew very little about Aboriginal culture or the depths of meanings held within the shimmering dots and mesmerizing lines. I proposed having an exhibition of Aboriginal artworks to Ian Hay, director of Saul Hay Gallery in Manchester, England, who shows my paintings, and he enthusiastically agreed. Just before the show opened, I read an article by Lord Frank Fields, founder of Cool Earth, whose vision to fight the climate crisis by protecting rainforests as well as helping indigenous people deeply resonated with me. Ian and I decided to donate 10% of all the sales to Cool Earth who provided posters and postcards which introduced more people to the amazing work that the charity does.

In 1998, a chance encounter in Australia led to my volunteering to transcribe the stories of a group of Aboriginal women artists at the remote outstation of Utopia in the country’s arid, red centre. I immediately found myself on a very steep learning curve about cultural difference. I realized that my culturally ocular-centric, aesthetic gaze had limited my perception and directly affected how I viewed the world. While walking with the women as they engaged in hunting and gathering, I often felt blind. The land disclosed so much more to them than it ever would to me. Being at Utopia disrupted my perceptions of time, the land, art, and of myself. Survival is a fine art at Utopia. I would not have survived without the women’s care. With patience and kindness, they taught me an embodied way of being on the land. Quite simply, I discovered the ground beneath my feet.

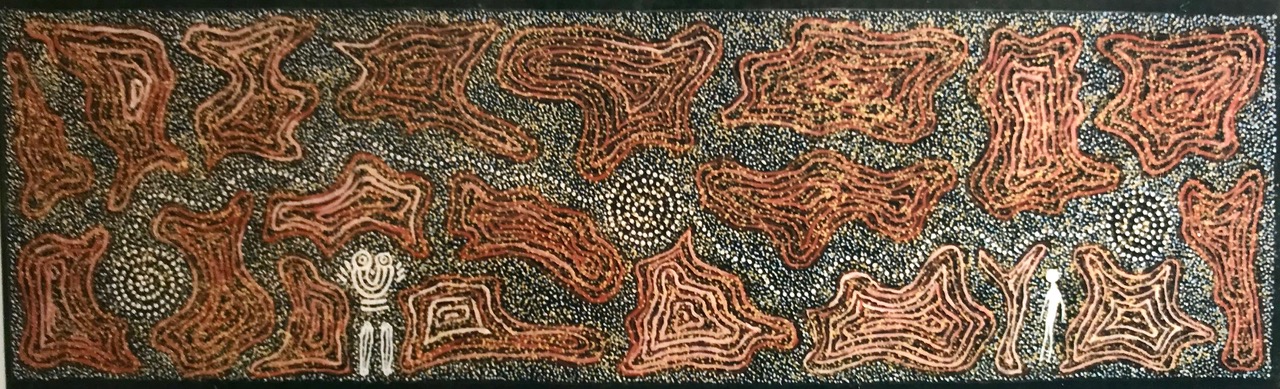

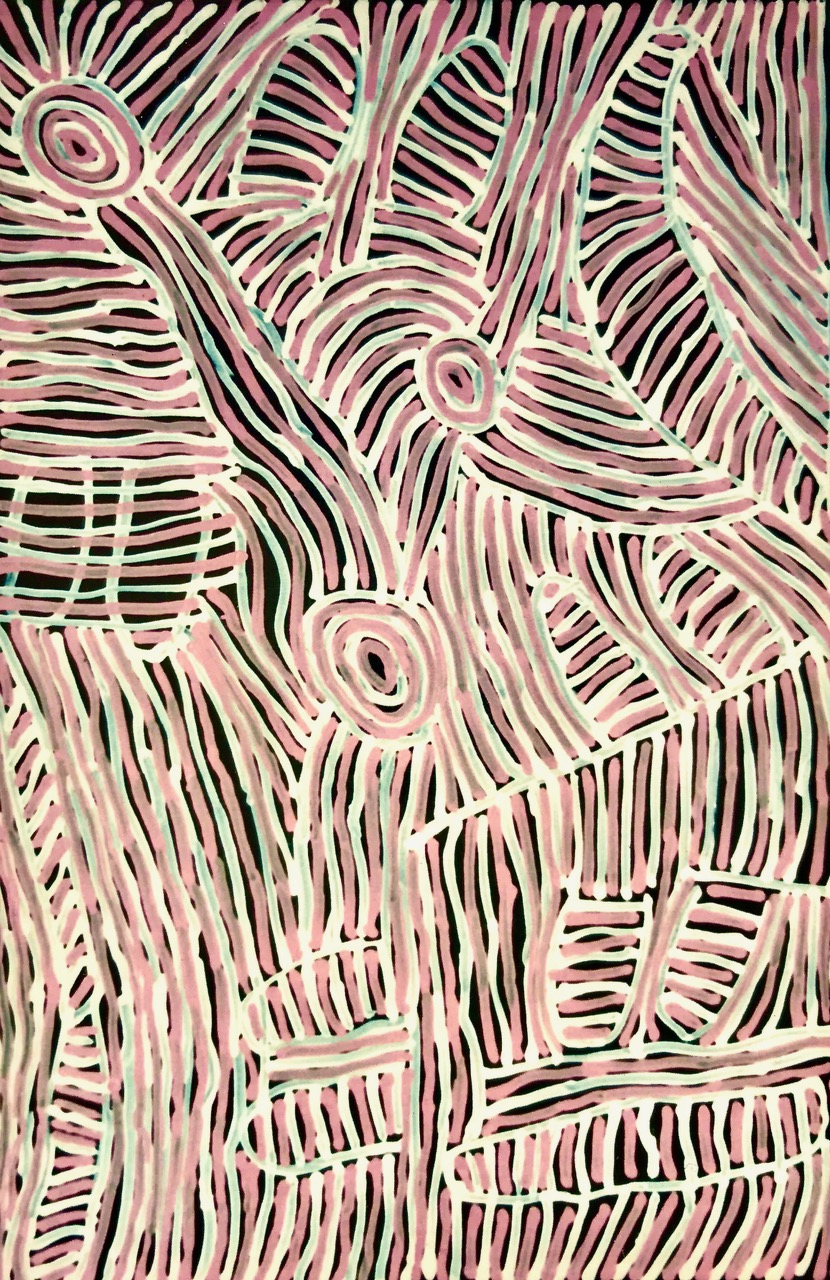

Culture, spirituality, land, kinship relationships, and art are not separate for Aboriginal Australians. They have the longest, continuous land-based culture in the world. For more than 65,000 years, they have been custodians for specific places, plants, and animals. Like many indigenous people, they have extraordinary ecological knowledge and experiential wisdom that ensures cultural continuity, survival, and well-being. They live traditional lives and hand down their oral culture and knowledge to new generations in ancient rituals. For Aboriginal people, Australia is a complex web of criss-crossing Dreamtime paths that connect the mythic past with the present. These paths form the basis of their art, creation stories, and song cycles that tell of mythological spirits that brought into being the flora, fauna, landforms, and elemental forces. Through paternal and maternal lineages, they receive totemic Dreamings which bestow custodial responsibilities. The Utopia women’s paintings in the exhibition were mainly of their Dreamings for Mountain Devil Lizard, Yam, and Bush Melon, and the awelye body painting designs made during women’s ceremonies. The men’s paintings incorporated symbols of their own sacred ceremonies.

Australian Aboriginal outstations are culturally rich but impoverished regions within a relatively affluent, primarily White country that is still largely in denial of historical and present-day injustices. When the first British fleet arrived in 1788, it was in their interests to wrongly declare the continent Terra Nullius. Seeing the land as infinite, without particularity, or only having real estate potential with no intrinsic significance as opposed to indigenous ways of seeing and experiencing the land as sacred reveals a fundamental difference of perception that continues to undermine mutual understanding.

EMILY KNGWARREYE. YAM FLOWER DREAMING. Acrylic on canvas. 62 X 47 CM.

There is so much that we can learn from indigenous cultures around the world about environmental custodianship, and so much more that we can do to help protect local people and their lands. With the worsening climate crisis, this is an urgent priority. Cool Earth’s work to protect rainforests which store carbon will have a direct influence on fighting global warming and benefit us all.

The exhibition was a great success in introducing people to Australian Aboriginal art and culture and to Cool Earth. Ian Hay and I were delighted that we were able to make a large donation to Cool Earth and raise awareness about its important work. I highly recommend incorporating into any event a donation to Cool Earth.

Paintings from the exhibition can be seen on Saul Hay Gallery’s website

Victoria King’s art and writing can be seen on her website

MINNIE PWERLE. AWELYE WOMEN’S CEREMONY. Acrylic on canvas. 97 x 60 cm.